In this case it’s literally a golden oldie, as the cartridge was gold (at least the earliest ones). And I still have that yellowing piece of plastic in my “cart box” but I didn’t actually need it this time (I sold my NES years ago anyway). This time, I booted the classic up on OpenEmu, an awesome new mac 8 and 16 bit emulator with masterly emulations of all the great 80s and early 90s systems (Gameboy, NES, SNES, Genesis, etc). Hey, and it’s fair use, because I did keep that cartridge (along with my other favorites).

For good reason, as The Legend of Zelda is one of the all time greats. A classic console game. A classic RPG. First in a legendary (haha) series and really one of the best games of all time, particularly when you place it into its context in the history of video games. Oh, and this time, I played it with my 5 year-old son. He mostly consulted from the arm of the chair (as the game is pretty hard), but he did love it, begging to play it day-in and day-out.

First a note on the emulation: Pretty much pitch perfect. I plugged a PS3 joypad into the Mac and the game looked, felt, and sounded exactly as it always did. The joypad controls are basically the same as a NES pad (except you don’t get that awful thumb burn the sharp plastic on the original led to). This is essential as emulated games require the right kind of controller. Console and arcade games are programmed for specific controllers — I should know, having shipped 9 of them! — and they just don’t play right unless the hardware/software pairing is nearly exact. The emulator also allows you to save your state, which isn’t necessary with Zelda, as it has a battery backup (also emulated), but certainly helps with other games.

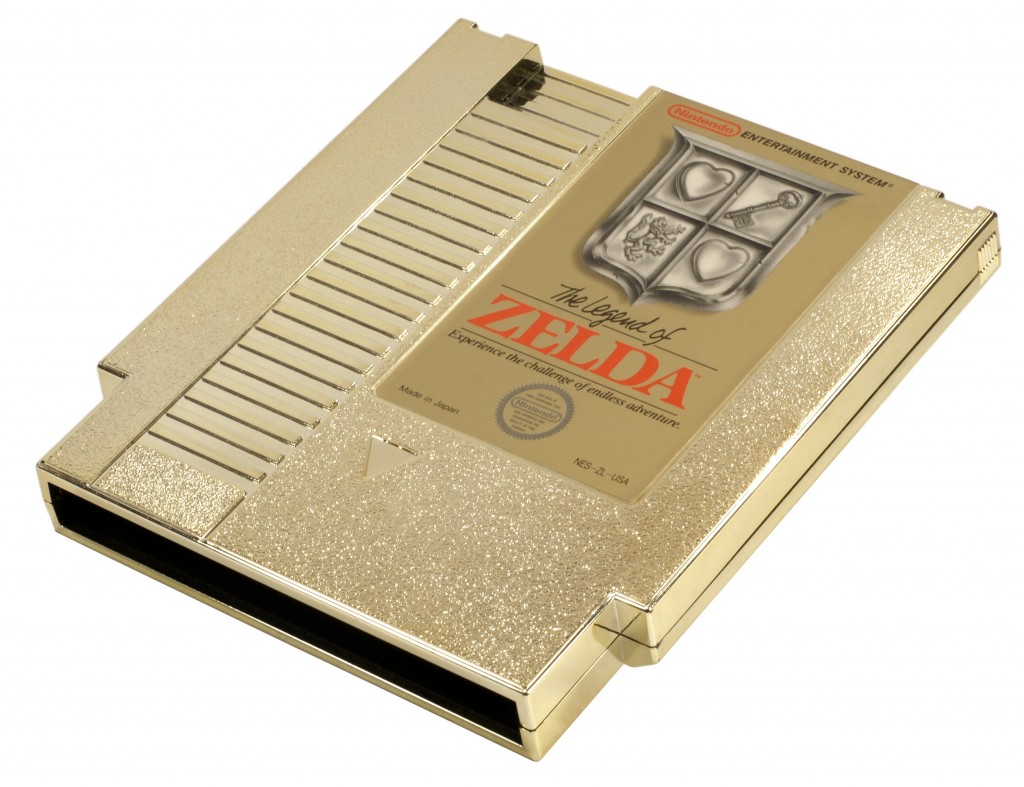

The original gold NES cart

So how was it? Surprisingly, hardly dated at all. Fantasy is my favorite genre, hell, I convinced my dad to buy the computer so I could write a D&D magnum opus. And early games like Wizardry, Alkabeth, and Ultima I, were among my computer favorites. Adventure (the original Atari 2600 cart game) was another old favorite and is the clear progenitor to Zelda. This notion of video game pedigree has long been of interest to me. Like any other human art, games borrow from those who came before. And there’s nothing wrong with this. To claim that Zelda is any less a work of genius because it shares elements with earlier fantasy games is pure hogwash. The good ones integrate and add to the oeuvre. We will call the Adventure/Zelda school, which also includes arcade game Venture and who knows how many others, the action RPG.

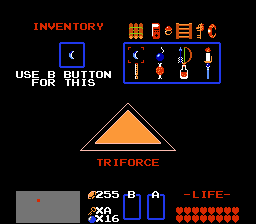

Zelda doesn’t have character stats or experience like Ultima and Wizardry (which borrow more heavily from D&D), but it does have a fantasy setting an an upgradable character. In fact, one of Zelda’s cooler features is its large number of items/powerups. You can up Link’s hit points (hearts), collect three swords, 2-3 shields, and a bevy of rings, bows, magic wands, and other magic items. I would argue that even a modern action dungeon crawler like Diablo III is a clear Zelda descendant.

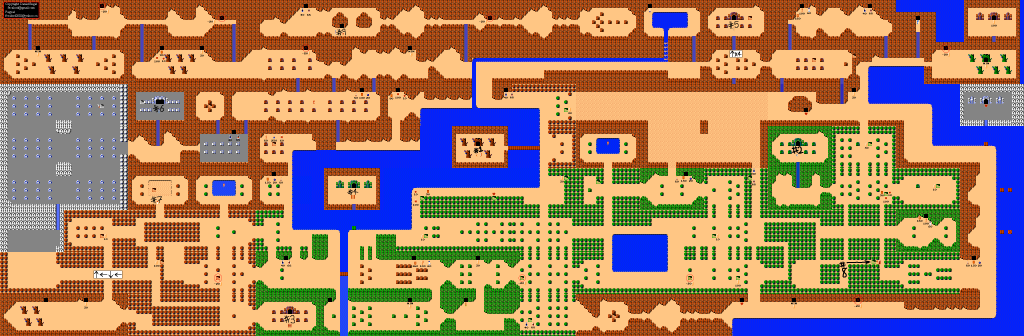

What Zelda does have is a big outside world, nine (x2 sorta) sprawling dungeons, a host of enemies, lots of secrets, and a tough but addictive joypad-based action gameplay. The map is positively gimongous by the standards of 1986. And this is many ways in which the gap between Adventure and Zelda is huge. Not only are there a lot of screens, but they actually look like something (Adventure‘s graphics are notoriously simplistic). The above map is comprised of 16×8 screens, each a bit different. The dungeons and various secret entrances and caves are tucked all over the place.

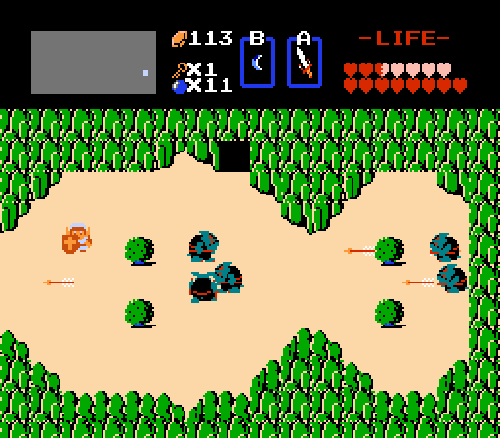

Wandering the outside takes up a good amount of time, with Link traversing between various dungeons and hunting for secrets. The outdoor enemies are tough at the start of the game, but easy enough once Link has powered up with the Blue Ring, Magic Shield, and some sort of distance weapon (the magic wand being one of the better ones). This brings me to one of Zelda’s design quirks. As the game progresses you increase the number of hearts (hit points), but when you die you always reset to three filled hearts. This necessitates visiting either a fairy or farming the monsters for hearts to reach full heath (often needed to get through a dungeon). And even odder by today’s standards, is the fact that only at full health can you fire the “beam sword” (launch your sword across the screen). This effectively makes the game “harder” when you’ve been hit, which goes against modern game design, but was typical of the more hardcore spirit of yesteryear. In fact, this whole setup isn’t so different from the typical arcade one in which you power up a life (typical in shooters like R-Type or even pseudo action RPG / platformer Ghouls and Ghosts). Zelda can be fairly unforgiving. The dpad control is a bit squirrelly, and the slightest bump against a foe or his flickery projectiles can cost you a heart (and your precious beam sword). It rewards patience and keeping your distance. Enemies randomly drop various gems (rupees), hearts, fairies, bombs, and the like. As my son put it, they can be “mean and stingy” (meaning that the RNG can really make or break you).

This also brings me to one of Zelda’s more peculiar design decisions. The world is littered with difficult to locate “secrets.” These stairs, caves, and the like are hidden behind indistinguishable spots all over the world that need to be bombed or “flamed” open. Inside are various powerups, vendors, quest items, and even dungeons. How the hell any “real” player (unaided) is supposed to find these? I have no idea. Today, in the age of the internet, one just uses a handy guide like this one. But in the 80s? We had to rely on Nintendo Power Magazine! This was one of Ninetendo’s dirty marketing tricks back then. Pretty much, to play these games, you had to have the right issue of Nintendo Power (with its dedicated hint guides). They used to sell millions of issues a month! I also read that producer and all around genius Shigeru Miyamoto wanted to create a game in which players had to “communicate and collaborate.” Well, I guess he did.

A typical dungeon room. Features: top door locked until all monsters are dead, left door locked with key, right wall busted open with bomb, boomerang hurling enemies

The dungeons are where most of the real difficulty is. Dying here brings you back to the start, but you keep anything you have acquired. Bombed out walls stay bombed, but monsters often/sometimes respawn. The problem is, you have to chose between slogging through another try with three hearts or heading out into the world to farm hearts, which will result in full respawns inside the dungeon. Later in the game judicious purchases of healing food and help here. Enemy difficulty is highly variable and while it does progress as you move through the game, it isn’t linear. Certain nasties like the Darknuts (can only be hit from behind/side) and the ghosts are far harder than others. The Like-Likes are positively mean, as they can steal your shield. Different rooms have different combinations and some can be quite frustrating (lots of Darknuts at the same time as fireball spitters!). Each dungeon has 1-2 magic items to acquire plus a compass and a map (which help fill in that screen in the upper left). At the end is a final boss, another heart container, and part of the “Triforce” (which although triangular, contains 8 pieces, so perhaps “Octforce” would have been a better name).

Each dungeon has a boss at the end. Each is seemingly difficult but usually possesses a “weakness” that while not always obvious, makes them fairly trivial. Some are vulnerable at different times or to different weapons (usually found in their own dungeon). This hydra guy above is more technique based, you have to strike each head 2-4 times (without getting hit by the fireballs). The earlier heads will “spin off” and attack you (just dodge them). Killing the last head will slay it. Basically, it’s all about the dodge and strike. Some bosses return in later dungeons as “sub bosses” with slightly different traits.

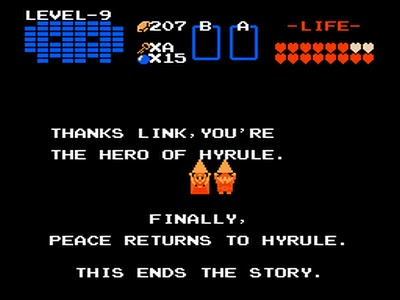

The game is light on plot: reassemble the Triforce, rescue the Princess Zelda, and save Hyrule. Better barely no plot than a dumb one that rubs itself in your face! Some of the messages along the way include bonus misspellings courtesy of their translation from the Japanese. Oh so fun!

All in all, Zelda remains intensely playable. While it might be a fairly frustrating at times, it’s never so hard that putting it aside for a couple hours doesn’t lead to immediate progress on returning. This is a pretty big game with a ton of variety, and it’s all packed into 128kb!! Yeah, that’s right, about the size of one highly compressed small internet jpeg ! Code, music, art, everything. And it was a big cart at the time, costing around $90-100 1986 dollars! Now it’s about the size of the average email in my inbox. There is even a “second quest” in which you can replay the game with a slightly different layout and higher difficulty.

Awesome game and a seminal mark in the history of the fantasy RPG. Even WOW owes a debt to Zelda.

My 5 year-old son Alex would like to offer his own review (typed completely verbatim):

When you play Legend of Zelda you go to a first dungeon, a second dungeon, a third dungeon, a fourth dungeon, a fifth dungeon, a sixth dungeon, a seventh dungeon, an eighth dungeon, a ninth dungeon and then you win the game. You might run into big bosses and scary Darknuts and ghosts and bats and blobs and bombs. And sometimes you can bomb a secret a door and collect keys and gems and hearts. Watch out to get no hearts or you start all over again. But after you finish the whole game on the nine dungeons you unlock the queen (Princess Zelda). And you won the game!

| If you liked this post, follow me at:

My novels: The Darkening Dream and Untimed |