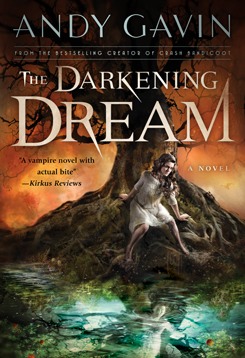

Chapter One:

Ignored

Philadelphia, Autumn, 2010 and Winter, 2011

My mother loves me and all, it’s just that she can’t remember my name.

“Call him Charlie,” is written on yellow Post-its all over our house.

“Just a family joke,” Mom tells the rare friend who drops by and bothers to inquire.

But it isn’t funny. And those house guests are more likely to notice the neon paper squares than they are me.

“He’s getting so tall. What was his name again?”

I always remind them. Not that it helps.

Only Dad remembers, and Aunt Sophie, but they’re gone more often than not — months at a stretch.

This time, when my dad returns he brings a ginormous stack of history books.

“Read these.” The muted bulbs in the living room sharpen the shadows on his pale face, making him stand out like a cartoon in a live-action film. “You have to keep your facts straight.”

I peruse the titles: Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Asprey’s The Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, Ben Franklin’s Autobiography. Just three among many.

“Listen to him, Charlie,” Aunt Sophie says. “You’ll be glad you did.” She brushes out her shining tresses. Dad’s sister always has a glow about her.

“Where’d you go this time?” I say.

Dad’s supposed to be this hotshot political historian. He reads and writes a lot, but I’ve never seen his name in print.

“The Middle East.” Aunt Sophie’s more specific than usual.

Dad frowns. “We dropped in on someone important.”

When he says dropped in, I imagine Sophie dressed like Lara Croft, parachuting into Baghdad.

“Is that where you got the new scar?” A pink welt snakes from the bridge of her nose to the corner of her mouth. She looks older than I remember — they both do.

“An argument with a rival… researcher.” My aunt winds the old mantel clock, the one that belonged to her mom, my grandmother. Then tosses the key to my dad, who fumbles and drops it.

“You need to tell him soon,” she says.

Tell me what? I hate this.

Dad looks away. “We’ll come back for his birthday.”

While Dad and Sophie unpack, Mom helps me carry the dusty books to my room.

“Time isn’t right for either of you yet,” she says. Whatever that means.

I snag the thinnest volume and hop onto my bed to read. Not much else to do since I don’t have friends and school makes me feel even more the ghost.

Mrs. Pinkle, my ninth-grade homeroom teacher, pauses on my name during roll call. Like she does every morning.

“Charlie Horologe,” she says, squinting at the laminated chart, then at me, as if seeing both for the first time.

“Here.”

On the bright side, I always get B’s no matter what I write on the paper.

In Earth Science, the teacher describes a primitive battery built from a glass of salt water covered in tin foil. She calls it a Leyden jar. I already know about them from Ben Franklin’s autobiography — he used one to kill and cook a turkey, which I doubt would fly with the school board.

The teacher beats the topic to death, so I practice note-taking in the cipher Dad taught me over the weekend. He shows me all sorts of cool things — when he’s around. The system’s simple, just twenty-six made-up letters to replace the regular ones. Nobody else knows them. I write in highlighter and outline in red, which makes the page look like some punk wizard’s spell book. My science notes devolve into a story about how the blonde in the front row invites me to help her with her homework. At her house. In her bedroom. With her parents out of town.

Good thing it’s in cipher.

After school is practice, and that’s better. With my slight build and long legs, I’m good at track and field — not that the rest of the team notices. A more observant coach might call me a well-rounded athlete.

The pole vault is my favorite, and only one other kid can even do it right. Last month at the Pennsylvania state regionals, I cleared 16’ 4”, which for my age is like world class. Davy — that’s the other guy — managed just 14’ 8”.

And won. As if I never ran that track, planted the pole in the box, and threw myself over the bar. The judges were looking somewhere else? Or maybe their score sheets blew away in the wind.

I’m used to it.

Dad is nothing if not scheduled. He and Sophie visit twice a year, two weeks in October, and two weeks in January for my birthday. But after my aunt’s little aside, I don’t know if I can wait three months for the big reveal, whatever it is. So I catch them in his study.

“Dad, why don’t you just tell me?”

He looks up from his cheesesteak and the book he’s reading — small, with only a few shiny metallic pages. I haven’t seen it before, which is strange, since I comb through all his worldly possessions whenever he’s away.

“I’m old enough to handle it.” I sound brave, but even Mom never looks him in the eye. And he’s never home — it’s not like I have practice at this. My stomach twists. I might not like what he has to say.

“Man is not God.”

One of his favorite expressions, but what the hell is it supposed to mean?

“Fink.” For some reason Aunt Sophie always calls him that. “Show him the pages.”

He sighs and gathers up the weird metallic book.

“This is between the three of us. No need to stress your mother.”

What about stressing me? He stares at some imaginary point on the ceiling, like he always does when he lectures.

“Our family has—”

The front doorbell rings. His gaze snaps down, his mouth snaps shut. Out in the hall, I hear my mom answer, then men’s voices.

“Charlie,” Dad says, “go see who it is.”

“But—”

“Close the door behind you.”

I stomp down the hall. Mom is talking to the police. Two cops and a guy in a suit.

“Ma’am,” Uniform with Mustache says, “is your husband home?”

“May I help you?” she asks.

“We have a warrant.” He fumbles in his jacket and hands her an official-looking paper.

“This is for John Doe,” she tells him.

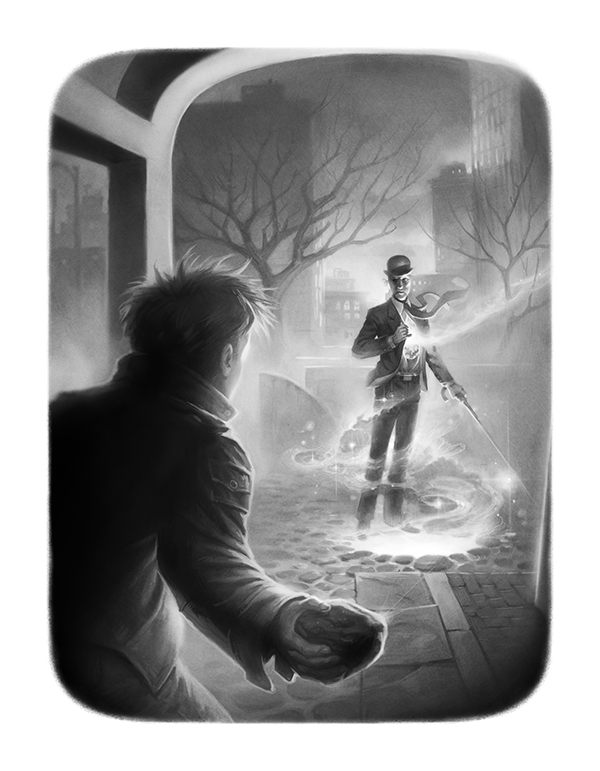

The cop turns to the man in the suit, deep blue, with a matching bowler hat like some guy on PBS. The dude even carries a cane — not the old-lady-with-a-limp type, more stroll-in-the-park. Blue Suit — a detective? — tilts forward to whisper in the cop’s ear. I can’t hear anything but I notice his outfit is crisp. Every seam stands out bright and clear. Everything else about him too.

“We need to speak to your husband,” the uniformed cop says.

I mentally kick myself for not ambushing Dad an hour earlier.

Eventually, the police tire of the runaround and shove past me as if I don’t exist. I tag along to watch them search the house. When they reach the study, Dad and Sophie are gone. The window’s closed and bolted from the inside.

All the other rooms are empty too, but this doesn’t stop them from slitting every sofa cushion and uncovering my box of secret DVDs.

Mom and I don’t talk about Dad’s hasty departure, but I do hear her call the police and ask about the warrant.

They have no idea who she’s talking about.

Yesterday, I thought Dad was about to deliver the Your mother and I have grown apart speech. Now I’m thinking more along the lines of secret agent or international kingpin.

But the months crawl by, business as usual, until my birthday comes and goes without any answers — or the promised visit from Dad. I try not to let on that it bothers me. He’s never missed my birthday, but then, the cops never came before, either.

Mom and I celebrate with cupcakes. Mine is jammed with sixteen candles, one extra for good luck.

I pry up the wrapping paper from the corner of her present.

“It’s customary to blow out the candles first,” Mom says.

“More a guideline than a rule,” I say. “Call it advanced reconnaissance.” That’s a phrase I picked up from Sophie.

Mom does a dorky eye roll, but I get the present open and find she did well by me, the latest iPhone — even if she skimped on the gigabytes. I use it to take two photos of her and then, holding it out, one of us together.

She smiles and pats my hand.

“This way, when you’re out on a date you can check in.”

I’m thinking more about surfing the web during class.

“Mom, girls never notice me.”

“How about Michelle next door? She’s cute.”

Mom’s right about the cute. We live in a duplex, an old house her family bought like a hundred years ago. Our tenants, the Montags, rent the other half, and we’ve celebrated every Fourth of July together as long as I can remember.

“Girls don’t pay attention to me.” Sometimes paraphrasing helps Mom understand.

“All teenage boys say that — your father certainly did.”

My throat tightens. “There’s a father-son track event this week.” A month ago, I went into orbit when I discovered it fell during Dad’s visit, but now it’s just a major bummer — and a pending embarrassment.

She kisses me on the forehead.

“He’ll be here if he can, honey. And if not, I’ll race. You don’t get your speed from his side of the family.”

True enough. She was a college tennis champ and he’s a flat-foot who likes foie gras. But still.

Our history class takes a field trip to Independence Park, where the teacher prattles on in front of the Liberty Bell. I’ve probably read more about it than she has.

Michelle is standing nearby with a girlfriend. The other day I tapped out a script on my phone — using our family cipher — complete with her possible responses to my asking her out. Maybe Mom’s right.

I slide over.

“Hey, Michelle, I’m really looking forward to next Fourth of July.”

“It’s January.” She has a lot of eyeliner on, which would look pretty sexy if she wasn’t glaring at me. “Do I know you from somewhere?”

That wasn’t in my script. I drift away. Being forgettable has advantages.

I tighten the laces on my trainers then flop a leg up on the fence to stretch. Soon as I’m loose enough, I sprint up the park toward the red brick hulk of Independence Hall. The teachers will notice the headcount is one short but of course they’ll have trouble figuring out who’s missing. And while a bunch of cops are lounging about — national historic landmark and all — even if one stops me, he won’t remember my name long enough to write up a ticket.

The sky gleams with that cloudless blue that sometimes graces Philly. The air is crisp and smells of wood smoke. I consider lapping the building.

Then I notice the man exiting the hall.

He glides out the white-painted door behind someone else and seesaws down the steps to the slate courtyard. He wears a deep blue suit and a matching bowler hat. His stride is rapid and he taps his walking stick against the pavement like clockwork.

The police detective.

I shift into a jog and follow him down the block toward the river. I don’t think he sees me, but he has this peculiar way of looking around, pivoting his head side to side as he goes.

It’s hard to explain what makes him different. His motions are stiff but he cuts through space without apparent effort. Despite the dull navy outfit, he looks sharper than the rest of the world, more in focus.

Like Dad and Sophie.

The man turns left at Chestnut and Third, and I follow him into Franklin Court.

He stops inside the skeleton of Ben Franklin’s missing house. Some idiots tore it down two hundred years ago, but for the bicentennial the city erected a steel ‘ghost house’ to replace it.

I tuck myself behind one of the big white girders and watch.

The man unbuttons his suit and winds himself.

Yes, that’s right. He winds himself. Like a clock. There’s no shirt under his jacket — just clockwork guts, spinning gears, and whirling cogs. There’s even a rocking pendulum. He takes a T-shaped key from his pocket, sticks it in his torso, and cranks.

Hardly police standard procedure.

Clueless tourists pass him without so much as a sideways glance. And I always assumed the going unnoticed thing was just me.

He stops winding and scans the courtyard, calibrating his head on first one point then another while his finger spins brass dials on his chest.

I watch, almost afraid to breathe.

CHIME. The man rings, a deep brassy sound — not unlike Grandmom’s old mantel clock.

I must have gasped, because he looks at me, his head ratcheting around 270 degrees until our eyes lock.

Glass eyes. Glass eyes set in a face of carved ivory. His mouth opens and the ivory mask that is his face parts along his jaw line to reveal more cogs.

CHIME. The sound reverberates through the empty bones of Franklin Court.

He takes his cane from under his arm and draws a blade from it as a stage-magician might a handkerchief.

CHIME. He raises the thin line of steel and glides in my direction.

CHIME. Heart beating like a rabbit’s, I scuttle across the cobblestones and fling myself over a low brick wall.

CHIME. His walking-stick-cum-sword strikes against the brick and throws sparks. He’s so close I hear his clockwork innards ticking, a tiny metallic tinkle.

CHIME. I roll away from the wall and spring to my feet. He bounds over in pursuit.

CHIME. I backpedal. I could run faster if I turned around, but a stab in the back isn’t high on my wishlist.

CHIME. He strides toward me, one hand on his hip, the other slices the air with his rapier. An older couple shuffles by and glances his way, but apparently they don’t see what I see.

CHIME. I stumble over a rock, snatch it up, and hurl it at him. Thanks to shot put practice, it strikes him full in the face, stopping him cold.

CHIME. He tilts his head from side to side. I see a thin crack in his ivory mask, but otherwise he seems unharmed.

CHIME. I dance to the side, eying the pavement, find another rock and grab it.

CHIME. We stand our ground, he with his sword and me with my stone.

“Your move, Timex!” I hope I sound braver than I feel.

CHIME. Beneath the clockwork man, a hole opens.

The manhole-sized circle in the cobblestones seethes and boils, spilling pale light up into the world. He stands above it, legs spread, toes on the pavement, heels dipping into nothingness.

The sun dims in the sky. Like an eclipse — still visible, just not as bright. My heart threatens to break through my ribs, but I inch closer.

The mechanical man brings his legs together and drops into the hole. The seething boiling hole.

I step forward and look down….

Into a whirlpool that could eat the Titanic for breakfast. But there’s no water, only a swirling tube made of a million pulverized galaxies. Not that my eyes can really latch onto anything inside, except for the man. His crisp dark form shrinks into faraway brightness.

Is this where Dad goes when he drops in on someone? Is the clockwork dude his rival researcher?

The sun brightens, and as it does, the hole starts to contract. Sharp edges of pavement eat into it, closing fast. I can’t let him get away. Somehow we’re all connected. Me, the mechanical man, Sophie, and Dad.

I take a step forward and let myself fall.

Chapter Two:

Yvaine

Unknown Locale

I fall hard onto wet cobblestones.

A pair of horses bears down on me fast. I roll into the gutter to avoid being trampled.

It’s seriously raining, a genuine Noah’s Ark deluge. Between the downpour and the low clouds, you’d hardly know it’s daytime.

The horses pass, drawing a covered coach behind them.

Coach?

The driver huddles in his cloak, a triangular hat pulled low against the downpour. Two flickering lamps hang from the vehicle’s rear.

Tourists ride coaches in Independence Park, and the drivers wear Revolutionary War outfits like this guy — but who takes a scenic ride during a rainstorm?

Then again, I just followed a clockwork man through a Hanna-Barbera hole.

I’d been halfway hoping the hole would lead to my father, but I look around and realize I’m the only one on the street — even the clockwork guy is long gone. Way to make my dad proud. Act after analysis, he’d say. Instead, I jumped into a wormhole to wherever.

And where is wherever? It’s a city street, a little like old Philly but there’s no sidewalk. Just a nasty strip of mud and refuse between the road and the building fronts. I take a few steps — and look down at my shoes, which are pinching my feet. Instead of sneakers I see old-fashioned black leather shoes crudely sewn and covered in mud, but they go with my waterlogged stockings, tattered knee-length pants, and ratty wool coat.

Like the coach driver or a mock pilgrim in the Thanksgiving Day Parade.

What the hell?

I limp down the empty street. The air seems different. January in Philly is always cold and dry, unless it’s snowing. Nothing like this slashing rain that makes me wish the Goretex jacket I put on this morning wasn’t lost in translation.

I hear my mother’s voice in my head: Get inside or you’ll catch cold.

While I don’t think you can catch the temperature, I better call her. Maybe even check the GPS and see where I am. I grope my strange pants and find the bulges made by my wallet and mobile. Rain and my new iPhone are not something I want to mix, but the nearby townhouses have covered porches like the ones on Society Hill.

I hop up a trio of marble steps to get out of the downpour, lean against a wooden column, and reach into my pocket for the phone.

But that’s not what I find. My fingers extract a small notebook covered in brown leather. I open it carefully, trying not to drip.

On the first page are some names written in blotchy ink. In my handwriting!

My name, my mom’s, our doctor’s, Dad’s, Aunt Sophie’s. The phone numbers and addresses underneath. On the next page is the embarrassing script that ought to be entitled The Tragedy of Charlie and Michelle — still enciphered. Whew!

I flip another page to find a charcoal sketch of my mother and me, posed exactly like that photo I took with my phone.

My life has always been pretty weird — like me. The ticking clock dude and the hole in the world were extremely weird.

But this is beyond weird. My mobile phone has mutated into a notebook!

I put it away and take out my wallet — um, leather pouch, full of silver and copper change. I don’t see any Washingtons or Jeffersons, only pirate coins.

I’m not dreaming. My wet clothes chafe against my skin, and when I run a finger down my jacket sleeve, I feel every bump in the rough wool. I study the street, easier on the porch without water pouring down my face.

Another carriage passes, this one with four horses and two drivers. A couple of people scurry along near the edges of the buildings trying their best to stay dry. A man helps a lady pick her way through the mud. She wears huge skirts and a bonnet. He’s sporting knickers, a long jacket, and a tri-corner hat atop his big white wig.

A spontaneous historic celebration? Magic mushrooms slipped into my Frappuccino? No, I’m me, and I’m not in Philadelphia. And I better find my dad or at least a way back, so I step out into the rain wishing I wasn’t the only one without a hat.

I make it about ten feet before the mud literally sucks one of my crappy shoes right off my foot. I kneel to pull it from the earth’s thieving grasp and someone collides with me from behind, knocking me face down into the muck.

“Pardon me, so sorry.” The accent is funny, but the voice is lilting.

I roll over to find a soaked rat of a girl backing away. Her dress is ragged and the yellow-brown hair escaping her bonnet is plastered against her filthy face. Even so, she stands out brightly against the drab cityscape.

“Where are we?” I ask.

Her eyes, too large for her face to begin with, seem to grow even larger.

Then she bolts down the street.

I try to knock the mud out of my shoe but the stuff is as thick as… mud.

And I notice my pants feel light — both my wallet-turned-purse and the phone-become-notebook are gone.

The girl is making good headway — she’s halfway down the block, running — and I notice her footprints have toes.

She’s barefoot and she picked my damn pocket!

I remember I’m only wearing one shoe, pull it off, and sprint after her in stocking feet.

In summer, at our shore house in Ventnor, I run barefoot on the beach every morning. This is like that, only colder, stickier, and way weirder.

“Give me back my stuff!” I yell after the girl.

She glances over her shoulder, lifts her skirts, then puts the pedal-to-the-metal — whip-to-the-nag? — and pulls even farther ahead. But that feeling comes over me, the one you get after a couple minutes of running when the pain goes away and you’re in the Zone and you think you can go on forever.

In no time, she’s only a few feet in front. The rain is letting up, but moisture hangs thick in the air, lending everything a dull blurry look. Except her. Bright legs stand out under caked mud. They pump furiously but she’s beginning to flag. She probably doesn’t run track. Not that they have track here.

Wherever — or whenever — here is.

She hooks a hand on an iron lamppost, whips herself around a corner, then we’re on another street, this one crowded with people and carts.

Everyone’s in costume. Yep. I’ve either dropped back two hundred years or gotten stuck in a rerun of Sliders.

I follow the girl’s bobbing head as she weaves through the crowd, often losing sight of her but finding her easily again thanks to her white bonnet and dirty-blond hair. She dodges to the side and ducks behind a cart piled with raw fish.

I pull up short. I noticed before, but now, breathing hard, I really notice.

This place stinks. Like horse shit, like cat piss, like dead fish. I can only imagine what it smells like on a day that isn’t cold and rainy.

I try to stay out of her sight but keep after her. I want the picture of Mom, and I’ll probably need the money. Which I’d still have if I’d remembered Dad’s oft-repeated advice: When you’re alone in a strange place, guard your things.

Even on his rare visits, he’s never been the take-your-kid-to-the-zoo type father. He and Sophie drove me to strange neighborhoods and made me find my way home without money or a phone. This charming family tradition started when I was, what? Five? No older than six, anyway.

I dodge past a well-dressed gentleman in a purple tailcoat and slide around the fish wagon.

No blond girl. “Damn!”

The vendor lady — a fishmonger? — glares at me.

Despite the setback, I feel giddy. I’m betting Dad’s aborted final lecture wasn’t about divorcing Mom or being an international super spy. No, he was going to tell me that in our family we run from clockwork cops and jump through holes in time.

Which would be extremely cool if the past didn’t smell like rotten fish and flies weren’t biting my ears.

The rain lightens to a drizzle. Beyond the fish wagon, scrappy retailers hawk cloth. I wander down the street, and it isn’t long before I catch the sound of the girl’s lilting voice. The few words I heard before made an impression, and she’s not speaking softly.

I find her in a courtyard, near a red and white brick church half covered in scaffolding.

This time I stay out of sight, peering around the edge of the gatepost. She’s talking to a man.

“Ben, you needs help me.”

He’s older, maybe twenty, and wearing the now-familiar knee-length pants and high socks. No jacket, just a loose white shirt and a leather apron. His long hair is tied back in a ponytail and he’s holding a silvery mug with black-stained hands.

“How do I even know it’s mine?”

“He’s yours,” the girl says, holding her arms rigid, her fists clenched.

This Ben guy shrugs.

Now that I’m not running headlong, I notice she really stands out. Not her street thief clothes, but her. Even the bare foot she’s stomping is crisper, more focused than the mud it splashes around.

“Who else would you have me turn to?” she says.

“Tipple of ale?”

The guy in the apron hands her the mug, which, surprisingly she drinks down as if it were water.

“Be reasonable,” he says. “I don’t even remember your name.”

My heart skips a beat.

She hurls the mug at his feet. “Yvaine!” she yells.

I can’t help but sympathize.

“Come again?” Ben says.

Her lips are frozen in frustration.

I might be sympathetic, but I still want my money back. Aunt Sophie had one thing to say about bullies: take the fight to them. I dash into the courtyard and grab the girl by the arm.

“Give me my stuff!”

She tries to twist away, but I hold firm.

“Ouch! Let go!”

The Ben guy’s hairline is beating an early retreat from his oval face. His generous forehead — more a fivehead — wrinkles in amusement.

“Who’s this? Another contender?”

“Charlie,” I say. “Charlie Horologe.”

Ben gives me the usual confused stare. He’s tall, a tad overweight but muscular.

“Doesn’t matter.” He turns from me to the girl. “You’ll have me believe I’m the only one, when this fellow comes looking after you.”

“She just picked my pocket on the street,” I say.

Ben smirks. “Watch out, boy, she knows more than one way to pinch a man’s purse.”

Yvaine is so red I think she might explode any second.

“But—”

Another young guy in an apron pokes his head out the church door.

“Mr. Franklin, the type’s ready for your approval.”

My eyes track Ben as he bows and heads inside. Ben Franklin? No way—

Yvaine slaps my face hard, scattering the gathering cloud of my thoughts. Bright specks wriggle across my vision and I nearly let go of her arm.

“You’ve ruined me proper!” She kicks at me with a filthy foot.

Close up she looks a little older than me, maybe sixteen, but much smaller, under a hundred pounds for sure. Her eyes are huge and really green, which almost makes her limp hair look that color too. A trickle of snot runs from one nostril.

“Hey,” I say. “You’re the one who stole my money!”

CHIME. The all-too-familiar sound echoes across the brick-boxed churchyard.

I feel Yvaine’s arm stiffen.

CHIME. The noise is slightly above us, to the left.

CHIME. I turn to see the clockwork man sitting on the wall of the courtyard. His suit is still blue, but his hat now has three corners. He’s holding something in his hand, like a book made of shiny brass, and his gaze flicks from it to us and back again.

CHIME. He puts the book away then unfolds upward to stand on the wall.

CHIME. He hops down into the yard. My insides knot. I found him. Or he found me.

CHIME. Yvaine screams. She tugs out of my grip and bolts toward the gate.

CHIME. I turn to see the clockwork man draw his sword. The mask of his face betrays nothing. Dad and Sophie probably had good reason to duck out when he knocked at the door.

CHIME. I sprint after Yvaine and pull the little gate shut as I pass. It isn’t locked or anything, but a few extra seconds can’t hurt.

CHIME. Glancing over my shoulder, I see the man standing behind the iron bars. His head pivots to follow me but he makes no move to open the gate.

We sprint through the cloth seller’s street. My nose stings: chemical fumes. With the rain dying down, more vendors have emerged, making our race more a slalom than a dash.

Yvaine is still moving, but I can see she’s running out of gas. She staggers into a cart and knocks a bundle of yellow cloth in the mud.

The owner hollers but she keeps going — and going — into an alley where she collapses onto a pile of garbage, gasping for air.

I’m breathing hard but doing fine — yay, four-hundred meter dash! — so I pounce and start patting her clothing.

“Watch the… hands!” She’s almost panting too hard to speak.

She looks pathetic, and I do feel bad — but not bad enough to stop groping her. I find her stash bound around her thigh and take back my purse and notebook.

But I return the three purses that aren’t mine.

She’s sobbing now and I feel even worse.

“I be cursed,” she says. “Men!” She kicks at me again. “You’ll ruin a girl, take her money. An’ a goddamned Tick-Tock?”

“Hey! I’m the victim here!”

The once-over she gives me is like my mother picking a watermelon.

“So when are you from, Charlie?”