Chapter One:

Agitation

Salem, Massachusetts, Saturday afternoon, October 18, 1913

As services drew to an end, Sarah peered around the curtain separating the men from the women. Mama shot her a look, but she had to be sure she could reach the door without Papa seeing her. After what he’d done, she just couldn’t face him right now. There he was, head bobbing in the sea of skullcaps and beards. She’d be long gone before he extracted himself.

“Mama,” she whispered, “can you handle supper if I go to Anne’s?” Last night’s dinner debacle had probably been Mama’s idea, but they’d never seen eye to eye on the subject. Papa, on the other hand, was supposed to be on her side.

Mama’s shoulders stiffened, but she nodded.

The end of the afternoon service signaled Sarah’s chance. She squeezed her mother’s hand, gathered her heavy skirts, and fled.

The journey through Salem’s bustling downtown took only ten minutes, but the Indian summer sun left her corset sticky and cruel. A final two blocks brought Sarah to her friend’s pre-Revolutionary house, a kernel of which dated to the seventeenth century. Wings, rooms, and gables had sprouted during the past two hundred years, and in its present form the house and stables were large enough for five family members, seven boarders, a decent collection of horses, and a dog.

Sarah entered without knocking. Mr. Barnyard, the Williamses’ obese basset hound, rushed to greet her. After suffering his affections, she found Anne in the sitting room helping her mother with the mending. Several inches taller than Sarah, she wore her straw-colored hair in two looped braids, and possessed all the womanly curves Sarah found lacking in herself.

“What a nice surprise,” Mrs. Williams said. “Sarah, I know you’re not much for the needle, but some conversation would help pass the time.”

Behind her mother, Anne stabbed herself in the chest with an imaginary dagger.

“I hate to disappoint you,” Sarah said, “but I hoped to steal away your oldest daughter. Where’s Emily? Can’t she help?”

Mrs. Williams shrugged a padded shoulder. “Out back somewhere. If I hadn’t whelped that one myself, I’d swear she’s some sort of changeling. But take Anne, she’s all thumbs today.”

Anne set down the trousers she was sewing and tugged Sarah out the door.

“Thank God,” she said, leading Sarah upstairs to the bedroom she shared with her younger sister. “It was so stuffy in there I thought my stitches might melt.” She cracked the window, sat on the bed, and patted the quilt next to her. “What’s brought you here on a Saturday? Shouldn’t you be helping your own mother?”

Sarah pulled the door closed and sat next to her friend.

“I had to talk to someone. Your brother isn’t going to barge in?”

“Sam’s earning extra money at the cotton mill. Tell me.”

“My parents ambushed me at Shabbat dinner last night.”

“That sounds exciting,” Anne said. “Attacked you with candles and loaves of bread?”

“Papa brought a man home with him unannounced. Not one of his usual cronies, a gentleman. In his twenties. His name was Chaim Hoffmann.”

Anne squealed. “That’s a mouthful. Was the fellow handsome?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Extra, extra! Sarah Engelmann forgot something!”

Sarah had to smile at that. She replayed last night’s dinner in her head, trying not to grimace as the awkwardness returned with the imagery.

In her mind’s eye, her parents and Mr. Hoffmann hung before her as vividly as if they sat in the room. His skin showed little evidence of exposure to the sun, his bearded face was thin, and his spectacles were twice as thick as her own.

Sarah blinked and the memory vanished. “Not handsome, not ugly.”

“Then his manner was bothersome?”

She shook her head. “Gentlemanly enough. Clearly he was very bright. A student of Papa’s friend.”

“So what’s the problem? Your mother married at eighteen. With your birthday coming up on us, your father’s probably barely reining her in.”

“I have to finish school,” Sarah said. “And at least begin college. What’s the point of having studied my whole life if all I do is settle down and start a family?”

“But it’s exciting just the same. At least you have prospects.”

“What are you talking about?” Sarah said. “Half the boys in school would cut off an arm to court you.”

Anne sighed. “Even the thought of choosing is stressful. If it were all arranged it’d be easy. You’re lucky.”

Lucky? Sarah couldn’t imagine one of Papa’s friends’ sons allowing her the freedom he did. Or the respect. They’d only want their table set and six brilliant sons to make them proud.

“I know what we should do!” Anne said. “With this heat and with your, um, stresses, we need a break. My lummox of a twin traded for a new filly this week. Why don’t the three of us go riding tomorrow, take a picnic, make a proper outing of it?”

Anne was right. School had started only a month ago, and Sarah’s life was already dominated by study.

“What time?” she said.

The girls drifted downstairs to find Mrs. Williams and Emily entertaining a boy in the parlor. So close to becoming a man, he looked to grow four inches if you glanced away.

Emily’s pink dress was disheveled but she appeared luminous just the same. Sarah worried about what was going to happen when she came into her own. Anne could be bold and outspoken, but she had a fundamental prudence entirely absent in her little sister.

The new boy rose to greet them. He was about the same age Sarah’s brother would’ve been and almost as handsome.

“Charles Danforth.” He extended his hand. His hair was much straighter than Judah’s.

“Nice to meet you,” Anne said, shaking hands. “You’re a friend of Emily’s?”

Emily looked like she wanted to take a bite out of someone.

“We both study Bible with Pastor Parris,” the boy said.

“Charles is just leaving,” Emily said. “He stopped by to bring us some of his mother’s preserves.”

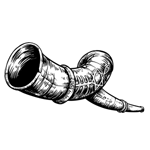

Charles offered Sarah his hand, and she took it. The late afternoon sun streamed in through the windows and threw their shadows against the wallpaper. A sound rose in her ears, slow and mournful like that of the shofar, the ceremonial ram’s horn blown to announce the New Year.

Sarah felt queer. Her mouth dry. Before her eyes the silhouettes on the wall contorted, human limbs and torsos shifting to form the shape of a leafless tree. The reddish hue of the sun — surely that’s what it was — made the tree look as if it was drenched in blood. The horn continued to sound in her ears, loud but seemingly blown at great distance.

She released Charles’ grip and the bloody tree vanished, in its place only the shadows of two young people who’d just shaken hands.

Chapter Two:

Dark Shadows

Near Salem, Massachusetts, Saturday evening, October 18, 1913

Charles trudged down the tree-shrouded lane, heading home. His visit to the Williamses hadn’t gone the way he hoped. Just last week Emily had offered to kiss him behind the chapel, then stomped on his foot when he tried. She really wasn’t very nice to him, but she brightened his time at church, in itself a small miracle. Just today — before she turned bratty — they’d been mocking the pastor’s habit of raising his voice as he said certain words, like damnation or purification.

Charles could see farmhouses in the distance and a half-collapsed old barn hunkered a couple hundred yards from the road. A rising chatter of high-pitched shrieking and leathery flapping made him stop and turn.

From the barn flew hundreds, perhaps thousands, of tiny dark forms. They poured out of gaps in the decrepit roof and high eaves like thick columns of smoke. Twisting languidly upward, they braided together into a larger column before passing overhead. He craned his neck to watch their crisp black silhouettes against the dusky sky.

Bats. Just bats living in an abandoned barn. They left their roosts at sunset, flying off to feed on the warm evening’s rich insect swarms. Charles took a deep breath and resumed his walk — more briskly than before.

Then he heard the voice.

The sound whispered in his head, not his ears, a soft caress made audible, issuing from all directions and none at all.

Stop, come to the trees. The tone was rich as milk straight from the pail, yet powerfully masculine. He stopped and walked off the road toward the trees. As he entered the darkening copse, a shadowy figure flitted from trunk to trunk.

Don’t look at me, keep walking. The figure winked at the edges of his vision as he continued forward. Why couldn’t he turn his head?

Here, stop. He stopped.

Someone approached from behind. A powerful scent encircled him, fragrances of damp earth and exotic spices, of cinnamon, honey, almonds. One hand reached from behind to clasp one of Charles’, the other placed itself on his hip — almost in an embrace.

Your chance has come. The beginning is as light as the end. Now the hand pulled Charles’ arm to the small of his back and jerked it upward, lifting him off the ground. A hideous, wrenching crack was accompanied by hideous, wrenching pain. His arm and shoulder burned. His gut spasmed, and he pitched forward, gasping.

Savor the feeling. On your wedding night, you must cut the cat’s head. The hand on his hip withdrew, leaving him dangling excruciatingly by his twisted limb. His attacker hadn’t come around, but somehow was now before him. Charles felt a hand almost caress him — then slap him brutally across the face. His head slammed sideways; nails tore into his skin. The pain knocked out any other sensation. He felt himself ebbing away. Like coals in an untended hearth, he was fading, and only the agony remained. He was dragged further from the road, tugged by a hand twisted into his hair. Charles fought to dig his heels into the earth, then fought not to yield to the blackness that rose to claim him….

It was the pain that woke him.

Everything was still dark. Everything in his body still hurt. He was seated on the bare earth, legs extended. His pants and shoes were gone, and he felt the leaves and dirt under his naked buttocks and heels. His shoulder screamed as his attacker, the man whose face he couldn’t see, stripped him of his shirt. Charles tried to lash out against limbs unyielding as ironwood. The man grasped his flailing hand, held it as a lover might, then bent the index finger back until Charles felt rather than heard the bone snap. Along with the pain came an absurd thought: so much for piano practice tomorrow.

The sacred hour has arrived. The passage stirs. Agony altered Charles’ perception, rendering his assailant in staccato images, like a picture-show projector cranked too fast. For all his strength the man wasn’t big, little taller than Charles himself. The only parts not clothed or swathed in black were his hands — and his face, featureless in the twilight but so pale it made Charles think of his dead grandmother’s sun-bleached snuff box feeding termites in the attic.

Rise to heaven. The man gripped his bare shins and lifted Charles into the air. His limp arm flopped painfully against the ground. He felt rough bark scrape against his naked back and rope burn his ankle as it was lashed to the tree. His face nearly kissed the man’s black suede boots, square-toed but with peculiar high heels. Again he tried to scream.

Quiet. His breath exhausted, only the smallest animal noise emerged from his throat.

One leg securely fastened, one leg to go.

Pain reminds you that you’re alive, the voice whispered. Two hands grabbed his free leg, one on the thigh, the other on the calf, and with another terrible crunch, the man twisted at odds to the direction of his knee. Blood seeped from where the bone pierced the skin.

A thousand pardons, I neglected to measure the tree. Charles vomited and then, because he was upside down, choked on it. Stomach acid drooled downward into his nostrils.

Gradually he became aware of a sound, a note from some titanic horn, slow and mournful, loud yet seemingly blown at great distance. He searched for its source. Below him — well, above him — was a brilliant dark orange and purple sky, clouds lit from the sides with an intense red light. Would that he could just step down into these cottony platforms. Hanging by his ankles, he could make out the gnarled roots of a great tree overhead. Warm tickles crawled across his face, dark liquid dripped off and fell upwards toward the twisted canopy of roots.

The man stood silhouetted against the luminous backdrop, his legs planted in the ground above forming a V, his features melding into the fading light.

Even in death, lost strength may be found. The man stepped toward him, and his dark shadow blotted out the heavens.